The crisis of COVID-19 has forced many students and employees to learn and work from their homes. Many Kentuckians took to this transition with ease. After all, they are used to connecting every day from the comfort of their own homes to friends, family, work, news, banking and more with the touch of a finger or click of a mouse. However, thousands of Kentucky’s rural citizens – many of which are in Eastern Kentucky – can’t say the same.

Their lack of broadband access can be encapsulated in a phrase that’s been used to describe the differences in accessibility of digital technology across the nation: the “digital divide”.

Recent research by the Community Economic Development Initiative of Kentucky explored the digital divide in each of Kentucky’s 120 counties.

Their research uses certain statistics to calculate a digital divide index score between 0 and 100 for each county, where a higher score indicates a higher divide – meaning less people have ease of access to digital technology.

For example, Carter County measured in at a digital divide index of 56.67, while Fayette County, which contains Lexington, the state’s second largest city, measured in at 14.61. In Fayette County, 13.9 percent of households are without internet subscriptions and 9.4 percent are without a computing device. Approximately 31 percent of Carter County households do not have internet subscriptions, and 25 percent of households do not have a computing device.

Compounding these divides is the fact that many rural areas have spotty cell service, at best, and none at all at worst.

Many rural Kentuckians rely on public places like libraries and community centers for wifi and computers in order to take care of critical business, such as employment resources, telemedicine services, and applying for and maintaining government benefits.

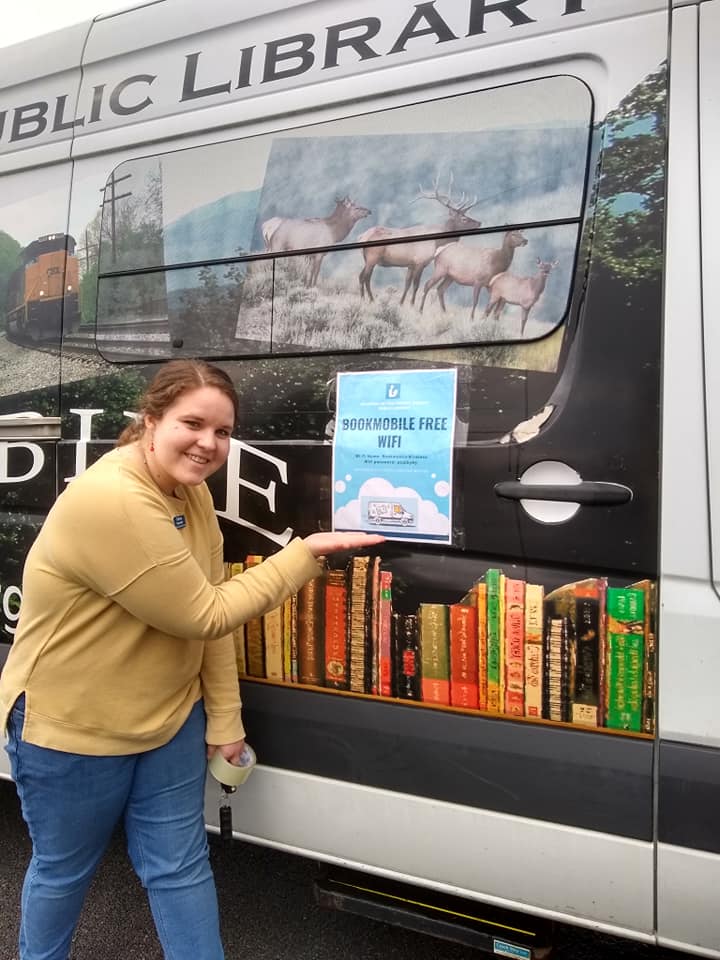

With COVID-19, many of Kentucky’s public facilities shut down overnight. However, libraries across the region, knowing how critical they are to so many families, sprang into action. The Estill County Library started special hours, allowing one person at a time to rotate in and out of their library so people can still apply for much needed unemployment benefits and other necessities, sanitizing the work station in between use. The Powell County Library created a public wifi zone in a parking lot using one of their mobile book vans.

While libraries are continually answering the call, their funding is always being threatened.

Photo by Lelia Martin of PRTC

The Kentucky House has proposed a budget this year that cuts state funding to libraries.

Library board member Michael Frazier said the Powell County Library gets about $13,000 a year in state funding, roughly the equivalent of its annual spending on electricity, adult programming or Internet connection. Local revenue contributes $275,000 each year for the library, which is most of its budget. With 22 percent of the county’s 12,442 people living in poverty, many families cannot afford a raise on their taxes.

“Each year, we’ve refused to raise taxes, relying on being effective with our resources and grants, because we know all too well that many families in Kentucky are just scraping by,” Frazier said.

Though public spaces, like libraries and wifi hotspots being offered by Gearheart Communications, Mountain Rural Telephone Cooperative and others, are filling a much needed void, these are not a long term solution for students and employees when they cannot go into school or work. Many Eastern Kentucky families do not have access to reliable transportation to get to these spaces. Even if they do, it is impractical to remain in a vehicle for extended periods of time to do homework, work or other necessities.

Additionally, on March 13, 2020, Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear issued an executive order requiring public boards and commissions to cancel in-person meetings, and instead use video teleconference technology, providing the public with a link to access the meeting remotely. Many public agencies have already begun to offer internet streaming for meetings prior to COVID-19. While this is an important tool to ensure accountability, transparency, and citizen participation in these important public meetings, the public must first have affordable access to the internet.

Rural communities have been patiently waiting for many years for broadband connection promised through the Kentucky Wired project. The project was supposed to construct more than 3,000 miles of high-speed, high-capacity fiber optic to every county in the state, but it has been overbudget and behind schedule for several years.

So, many communities have pursued other solutions.

Jackson County was recently featured in The New Yorker with an article titled “The One-Traffic-Light Town with Some of the Fastest Internet in the U.S.” Peoples Rural Telephone Cooperative, which covers Jackson and Owsley Counties, used Obama-era stimulus money combined with loans to upgrade their lines to what is required for high-speed internet. Mountain Telephone, based in West Liberty, has also upgraded their systems and offers high-speed internet to their clients in 10 counties.

As we work to build Appalachia’s New Day, especially in light of the COVID-19 crisis, we must also hold public officials accountable in efforts to bring affordable broadband to all corners of our state. We must also keep in mind the important role libraries, community centers and other public spaces play in bridging the digital divide and strive to keep these programs well-funded.

Read an op-ed on this topic by Peter Hille, MACED’s president, here.

About this campaign: This is story #53 in the Appalachia’s New Day series, a new storytelling effort launched in June 2019 by MACED for Eastern Kentucky communities. We can work with you to help identify, shape and amplify stories about businesses, programs and initiatives in your community that are helping build a new economy. Read more stories here. Contact us or sign up here if you would like more details.

To stay informed about Kentucky Wired, subscribe to the Miswired newsletter, a joint investigation by Kentucky’s Louisville Courier-Journal and ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network.