The secret is out — Kentucky is the place to be.

Large swaths of land across the state are being eyed for new developments of all kinds, including a controversial one: solar farms. At least 50 new large-scale solar projects have been proposed here since 2020, primarily due to new federal incentives and the increased affordability of renewable energy. Often, these farms are supported by Fortune 500 companies looking to purchase the energy. For example, Toyota is the primary buyer for energy generated at the 900-acre solar farm nearing completion on a former coal mine in Martin County. But now that the economics of large-scale renewable energy are penciling out when compared to adding new fossil fuel plants, utility companies themselves are also looking to add solar as a power source in their traditionally coal and gas heavy portfolios.

East Kentucky Power Cooperative is a nonprofit utility owned by 16 cooperatives, serving more than 1 million Kentuckians across 89 counties. They’ve been getting their energy from two coal-powered plants, two natural gas plants, six landfill gas generation facilities, two hydroelectric facilities (via what’s called a power purchase agreement), and, as of 2017, one solar farm. This spring 2024, however, they proposed building two additional solar farms, one in Lexington measuring 388 acres and one in Marion County measuring 635 acres. This has caused increased debate by Kentuckians who cite concern with ‘prime’ land being dedicated to fixed solar panels versus other uses, like farming or housing.

At the Mountain Association, the nonprofit where I work, we’ve been shouting (literally from the rooftops) for years that we think distributed solar is the way to go – this means solar on or near buildings or homes that directly use the bulk of that energy right there on site – versus large-scale farms. Rooftop or other small-scale solar makes use of unused space, and creates a tangible difference on the business’s or resident’s bills. In this work, we’ve also found ourselves at the table with large-scale solar developers as we look to advocate for communities.

Because we serve Eastern Kentucky, most of these conversations are about building solar farms on abandoned surface mine land, which Kentucky has more than 300,000 acres of, according to a new report from The Nature Conservancy. Often this land isn’t suitable for much due to soil instability and other issues. We have come to appreciate the role of large solar farms in the fight against skyrocketing utility rates, climate change, pollution, and even their role in protecting farmland.

In intervening in Louisville Gas & Electric and Kentucky Utilities’ recent proposal to build two new gas-powered plants, we dug into data that proves again and again how much better renewables are for safe, healthy job prospects for energy workers, for the health of residents who live near installations, and for water sources, farmland, and overall climate. Additionally, report after report shows that renewables are cheaper than coal, and likely cheaper than gas, especially in the long run. Many corporations are also actively seeking to locate near clean energy sources, so these projects can function as a key economic development tool to attract job creators. For example, Maker’s Mark will be purchasing solar from EKPC in the near future.

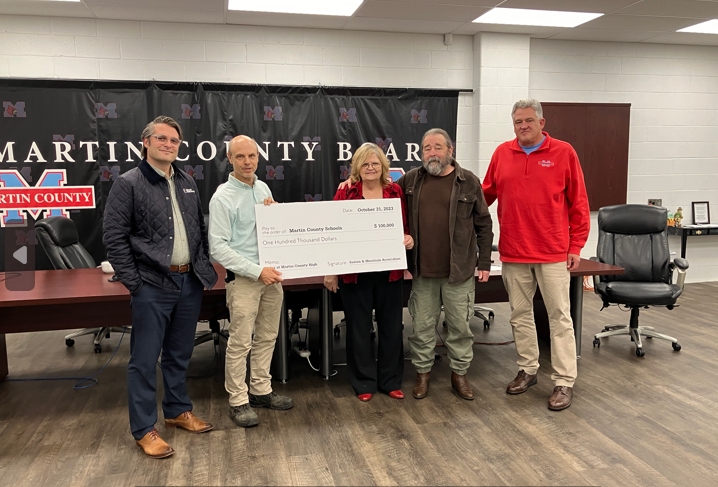

Because coal and natural gas aren’t the answer, we must look at large-scale renewables despite not being perfectly idyllic. In discussions with solar developers, we’ve advocated for community benefits agreements to be worked into deals so surrounding residents see some gain from these developments, especially since the energy is usually sold to large corporations or entities outside the local area, and since they generate few long-term jobs. Community benefits agreements, mandated if a project is using new federal incentives — as EKPC is likely to do for the Lexington and Marion County projects — are a way for community members to benefit from these farms. These are legally binding contracts between developers and municipalities or local community groups. For example, in Martin County, we worked with the developer to grant Martin County High School $100,000 toward a solar installation at the local high school.

If you are impacted by any of these developments, we encourage you to participate in public hearings and file public comments in order to weigh in on things that are important to you. Find information on the October 29 public hearing for the EKPC projects here: https://psc.ky.gov/.

Chris Woolery is the Energy Projects Coordinator at Mountain Association. He can be reached at chris@mtassociation.org.

This is an op-ed that appeared in several Kentucky papers in October 2024.